During the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, over 75% of peer-reviewed studies about transmission patterns relied on hypothesis testing to separate fact from speculation. This explosion of data-driven analysis revealed how statistical methods shape critical decisions in high-stakes environments.

Modern organizations face a similar challenge: transforming raw numbers into reliable conclusions. Two foundational tools dominate this process, each offering distinct advantages for validating assumptions. While often overshadowed by machine learning trends, these methods remain indispensable for minimizing guesswork.

The choice between these approaches determines whether teams uncover genuine patterns or chase statistical ghosts. Consider how e-commerce giants optimize checkout flows—their A/B tests hinge on selecting the right validation framework. A misapplied method could cost millions in lost revenue.

Key Takeaways

- Hypothesis testing forms the backbone of data-driven decision-making across industries

- Proper test selection prevents false conclusions in business analytics

- Statistical validation converts raw data into strategic advantages

- Real-world applications range from clinical trials to algorithmic auditing

- Methodology differences impact result reliability and interpretation

This exploration clarifies when and how to leverage these powerful techniques. We’ll dissect their mechanics through practical scenarios, equipping professionals to choose wisely in fast-paced environments where evidence trumps intuition.

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

Every day, businesses make critical decisions that shape their future – but how many base these choices on verifiable evidence? Hypothesis testing transforms gut feelings into actionable intelligence through a structured four-phase approach:

What Is Hypothesis Testing?

This method compares observed outcomes against expected results using statistical principles. The process follows these steps:

- Define competing claims: null hypothesis (existing reality) vs alternative (proposed change)

- Establish significance thresholds (α values) reflecting risk tolerance

- Calculate test statistics from sample data

- Determine whether results justify rejecting the null hypothesis

Its Role in Data-Driven Insights

Modern analytics teams use this framework to validate everything from marketing strategies to operational changes. Consider these applications:

- Evaluating website redesign impact on conversion rates

- Testing new manufacturing techniques for defect reduction

- Assessing customer satisfaction changes after service upgrades

Proper implementation requires understanding when to use specific methods. Teams often consult resources like statistical test comparisons to avoid analysis pitfalls. By converting raw numbers into validated conclusions, organizations reduce decision risks while accelerating innovation cycles.

Fundamentals of Z-tests

Pharmaceutical researchers faced a critical challenge last year: determining if a new drug’s effectiveness differed significantly from existing treatments. Their solution? A statistical approach built on decades of proven methodology. Z-tests provide this precision when two conditions align—either exact population parameters exist or substantial data quantities create reliable approximations.

Key Concepts and Calculations

The z-test’s power stems from its connection to the standard normal distribution. This bell-shaped curve becomes predictable when sample sizes exceed 30 observations, thanks to the central limit theorem. The formula Z = (x̄ – μ₀)/(σ/√n) transforms raw data into standardized scores, allowing direct probability comparisons.

Consider a national retailer analyzing checkout times. With historical population standard deviation data from 500 stores, managers calculate z-scores to identify statistically significant changes after process improvements. This mathematical framework converts operational metrics into actionable insights.

When to Choose a Z-test

Two scenarios demand this method: known population variance or large datasets with estimated parameters. Quality control engineers frequently use the first condition—manufacturing specs often provide precise tolerance ranges. Market researchers leverage the second, where survey responses from thousands create stable estimates.

A common pitfall arises when teams confuse sample-based estimates with true population values. Banking institutions avoid this by using decades of loan default rates as their σ reference. When these parameters remain uncertain and samples stay small, alternative methods become necessary.

Understanding T-tests: When to Use and Why

Startups often face a critical dilemma: validating ideas with limited data. When population variance remains unknown and datasets stay under 30 observations, professionals turn to a specialized approach. This method thrives where uncertainty dominates, using sample-derived estimates to navigate incomplete information landscapes.

One-Sample vs Two-Sample Applications

The one-sample version answers foundational questions. Teams compare collected data against theoretical values—like testing if a new sales tactic matches predicted performance. The formula T = (μ – μ₀)/(s/√N) quantifies deviations from expectations.

Two-sample analysis drives comparative decisions. Marketing departments rely on it to evaluate campaign variations, using T = (μ₁ – μ₂)/√((s₁²/N₁)+(s₂²/N₂)) to measure genuine differences between groups. This framework prevents false positives when assessing feature updates or pricing strategies.

Mastering Limited Data Scenarios

Small samples demand rigorous safeguards. The t-distribution’s wider tails automatically compensate for increased variability—a mathematical insurance policy against overconfidence. Clinical trials exemplify this need, where patient recruitment costs necessitate working with restricted datasets.

Financial analysts apply these principles when evaluating niche markets. With sparse historical data, they calculate conservative confidence intervals that reflect true uncertainty. This approach maintains statistical integrity while enabling actionable insights from imperfect information.

For teams navigating these waters, resources like our comparative analysis of these methods provide crucial guidance. The right technique transforms constrained data into strategic clarity, proving that size isn’t everything in statistical validation.

Assumptions Behind Z-tests and T-tests

What separates reliable insights from flawed conclusions in data analysis? The answer lies in rigorously testing foundational assumptions before interpreting results. Valid statistical outcomes depend on meeting specific conditions that govern each method’s accuracy.

Standard Deviation: Population Knowledge vs Sample Estimates

Population standard deviation acts as a critical differentiator. When known precisely—like established manufacturing tolerances or decades of financial data—it enables precise z-score calculations. This parameter often comes from complete historical datasets or controlled environments.

Sample standard deviation enters the equation when working with new variables or limited information. Here, t-tests automatically account for estimation uncertainty through adjusted confidence intervals. Marketing teams analyzing emerging markets frequently encounter this scenario.

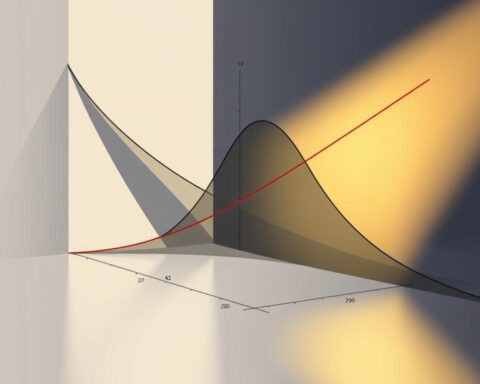

Shapes of Certainty: Distribution Fundamentals

The normal distribution’s symmetrical bell curve underpins z-test validity, assuming predictable spread patterns. In contrast, the t-distribution’s heavier tails provide built-in protection against small sample variability. These differences become visually apparent when comparing probability density curves.

| Test Type | Standard Deviation | Distribution | Sample Size | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-test | Population known | Normal | ≥30 preferred | Stable |

| T-test | Sample estimated | Student’s t | <30 typical | Adjusts for uncertainty |

Diagnostic tools like Q-Q plots help verify normal distribution compliance. For smaller datasets, the t-distribution’s flexibility prevents false confidence in marginal results. Both methods require independent observations—a non-negotiable condition ensuring statistical validity.

Application and Examples of Z-tests

Educational institutions face pressing questions when evaluating student performance. How can administrators confirm whether new teaching methods actually improve outcomes? Z-tests offer concrete answers through structured analysis of academic benchmarks.

Benchmark Verification in Education

Consider a district assessing if female students exceed national math averages. With a population mean of 600 and known standard deviation (100), administrators collect 20 scores showing a sample mean of 641. The test statistic calculation:

- Z = (641 – 600) / (100/√20) = 1.83

- Critical value at α=0.05: 1.645

Since 1.83 > 1.645, results indicate significant performance improvement. This one-sample z-test approach helps schools validate curriculum changes against established standards.

Market Research Comparisons

Consumer brands frequently compare demographic groups. A company testing gender-based score differences might use a two-sample z-test with these parameters:

| Group | Mean Score | Population SD | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | 641 | 100 | 20 |

| Boys | 613.3 | 90 | 20 |

Calculating Z = 2.326 against the critical 1.96 confirms a statistically significant 10-point difference. Such analysis prevents costly misjudgments in product targeting.

These examples demonstrate how professionals apply Z-tests across sectors. From quality control checks to policy evaluations, the method converts numerical data into decisive evidence when population parameters are known. Proper implementation requires balancing mathematical rigor with practical interpretation—a skill that separates data-informed decisions from guesswork.

Application and Examples of T-tests

Corporate trainers faced skepticism when claiming a new program boosted sales—until numbers told the story. One-sample analysis shines when organizations need to validate changes without full population metrics. This approach turns limited observations into decisive evidence.

Validating Training Effectiveness

Consider a retail chain testing a sales workshop. Historical data shows a mean population of $100 per transaction. After training 20 employees, the sample data reveals a $130 average with $13.14 sample standard deviation.

The calculation unfolds in three steps:

- Compute standard error: 13.14 / √20 = 2.94

- Determine t-score: (130 – 100) / 2.94 = 10.2

- Compare against critical value (α=0.05, df=19): 1.729

With the t-score exceeding the threshold, results confirm significant improvement. This process works precisely because we don’t know population parameters—the exact scenario demanding t-tests over other methods.

Real-world applications extend beyond sales. Healthcare administrators use similar frameworks to evaluate patient outcomes after protocol changes. Tech teams assess feature updates using pre/post deployment comparisons. The method’s adaptability makes it indispensable for data-driven decision-making.

Key implementation considerations:

- Baseline measurements must reflect stable historical patterns

- Sample selection should represent broader populations

- Confidence intervals require careful interpretation

By embracing this structured approach, professionals transform uncertainty into actionable insights. The mathematical rigor prevents false victories while spotlighting genuine progress.

T-tests and Z-tests: Detailed Comparison

Imagine two labs analyzing the same clinical trial data—one reaches groundbreaking conclusions while the other wastes resources. The difference often lies in selecting the proper validation framework. Understanding how these methods align and diverge turns statistical theory into competitive advantage.

Shared Foundations of Inference

Both approaches anchor decisions in hypothesis testing principles. They start by defining a null hypothesis representing no effect, then calculate the probability of observed results occurring by chance. This shared structure allows consistent interpretation across studies—whether analyzing drug efficacy or customer behavior shifts.

The mathematical engines powering these tests show striking parallels. Their formulas both measure how far sample means deviate from expectations, scaled by variability metrics. This similarity explains why professionals often use them interchangeably—until hidden assumptions surface.

Diverging Paths in Practice

Three critical factors dictate test selection:

- Data maturity: Known population parameters unlock z-test precision

- Sample constraints: Under 30 observations? T-tests adjust for uncertainty

- Risk tolerance: T-distributions provide wider confidence intervals

Consider a tech startup analyzing user engagement. Without historical variance data and limited early adopters, the t-test becomes their only viable option. Contrast this with established e-commerce platforms—their massive datasets justify z-test efficiency.

These differences impact result reliability. A significant difference found via z-test with estimated parameters might vanish under t-test scrutiny. Professionals who grasp these nuances avoid costly misinterpretations while building stakeholder trust in data-driven strategies.

Choosing the Right Test for Your Data

Selecting the optimal validation method requires balancing precision with practicality—a skill that separates data masters from spreadsheet jockeys. Professionals face this crossroads daily: when does sample size demand simplicity, and when does uncertainty require adaptive rigor?

Strategic Selection Through Key Criteria

Two factors dictate ideal test selection. First, the availability of population variance knowledge—established parameters enable precise calculations. Second, observation counts—large sample scenarios (n>30) often permit approximations even without full population data.

Consider these guidelines for confident decisions:

Reach for z-tests when working with verified historical metrics or substantial datasets. Manufacturing quality checks using decades of specs exemplify this scenario.

Opt for t-tests when exploring new variables with limited observations. Startups analyzing pilot programs with 20 users typify this need for conservative estimates.

As datasets grow beyond 30 points, both methods converge. Sample variance becomes reliable enough to approximate population parameters—the t-distribution gradually mirrors the normal curve’s predictability. This mathematical harmony allows flexibility in large-scale analyses while maintaining statistical integrity.

FAQ

How do I decide between a Z-test and a T-test?

Use a Z-test when you know the population standard deviation and have a large sample size (typically ≥30). Choose a T-test for smaller samples or when population variance is unknown. Both compare sample means to population means but differ in data requirements.

What happens if I ignore normal distribution assumptions?

Violating normality can lead to inaccurate p-values, increasing the risk of false conclusions. Z-tests assume a standard normal distribution, while T-tests use the heavier-tailed t-distribution to accommodate small sample uncertainties.

Can I use a Z-test with sample standard deviation?

Only if the sample size is sufficiently large (n≥30) due to the Central Limit Theorem. For smaller samples, replace the Z-test with a T-test, which adjusts calculations using sample standard deviation.

Why do T-tests handle small samples better?

The t-distribution accounts for increased variability in small datasets by having wider confidence intervals. This adjustment reduces the chance of Type I errors when population parameters are estimated from limited data.

What’s a real-world scenario for a two-sample Z-test?

Comparing average sales between two regional stores with known historical variances. For example, testing if a new marketing strategy caused a significant difference in revenue using large, stable datasets.

When should I worry about population variance in hypothesis testing?

It’s critical for Z-tests, which require known population variance. If variance is unknown, T-tests are safer—they use sample variance and adapt to uncertainty, especially with limited data points.

How does rejecting the null hypothesis differ between these tests?

Both use p-values against a significance level (e.g., α=0.05), but T-tests have higher critical values due to wider confidence intervals. This makes rejecting the null slightly harder with small samples unless the effect size is strong.

Are there alternatives if my data isn’t normally distributed?

For non-normal data with small samples, consider non-parametric tests like the Mann-Whitney U test. Large samples (n≥50) may still use Z-tests due to the Central Limit Theorem’s robustness.