Did you know 73% of flawed research conclusions stem from incorrect analysis methods? In an era where decisions hinge on data-driven insights, choosing the right tools to interpret information isn’t just helpful—it’s nonnegotiable.

These analytical tools act as gatekeepers of credibility, transforming raw numbers into actionable knowledge. Whether validating hypotheses or identifying trends, their role extends far beyond calculations—they shape how we understand patterns in everything from drug trials to market trends.

However, not all approaches are equal. A poorly chosen method can distort results, leading to costly errors. By understanding how these frameworks work, professionals gain the power to turn uncertainty into clarity—and assumptions into evidence.

From healthcare breakthroughs to AI advancements, the ability to analyze datasets confidently separates innovators from followers. This guide explores how mastering these techniques unlocks precision in research while avoiding common pitfalls.

Key Takeaways

- Proper analysis methods validate hypotheses and reduce errors in conclusions

- Test selection directly impacts the reliability of research outcomes

- Mathematical frameworks transform raw data into evidence-based insights

- Incorrect approaches can lead to misleading interpretations of patterns

- Modern applications span industries, from tech to pharmaceuticals

Overview of Statistical Testing in Scientific Research

Every research breakthrough begins with a critical analytical step. This process transforms raw observations into validated evidence through structured methods that separate meaningful patterns from background noise. At its core, statistical analysis serves as a truth-seeking mechanism—answering whether observed effects reflect reality or random chance.

Two frameworks guide this exploration. Descriptive statistics summarize data through averages or distributions, while inferential techniques test hypotheses and predict broader trends. For example, comparing drug effectiveness between patient groups reveals treatment impacts. Correlation studies might expose hidden links between environmental factors and health outcomes.

Modern applications extend beyond basic comparisons. Regression models forecast outcomes based on multiple variables—essential for climate predictions or financial modeling. Agreement assessments ensure measurement tools produce consistent results across labs or technicians. Specialized approaches like survival analysis track event timelines, crucial in medical trials studying disease progression.

These tools create an objective framework for decision-making. By calculating probabilities rather than relying on intuition, researchers minimize bias in their results. This rigor transforms tentative observations into foundations for innovation—whether improving AI algorithms or validating renewable energy solutions.

Foundational Concepts in Statistics

Clear analysis begins with knowing your tools. Like architects studying materials before building, researchers must grasp data characteristics and distribution patterns to construct reliable conclusions.

Levels of Measurement and Data Types

Four measurement tiers shape analytical possibilities:

| Measurement Level | Characteristics | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ratio | True zero + equal intervals | Weight, height |

| Interval | Equal intervals, arbitrary zero | Temperature (°F) |

| Ordinal | Ordered ranks, unequal gaps | Survey ratings (1-5 stars) |

| Nominal | Categories without order | Eye color, blood type |

Understanding Mathematical Distributions

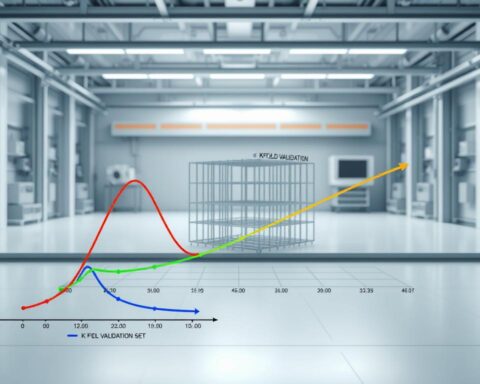

Patterns in numbers tell stories. The classic bell curve—normally distributed data—governs many natural phenomena. For example, human heights cluster around averages with predictable tapering.

Different distributions unlock unique insights. Skewed models reveal income disparities, while binomial patterns track success rates in clinical trials. Choosing wrong frameworks risks misinterpretation—like using linear assumptions for exponential growth.

Mastering these principles streamlines model-building. As explored in data analysis methods, proper categorization prevents flawed comparisons between apples and oranges—or in statistical terms, between interval and ordinal variables.

Choosing the Right Statistical Test

How do researchers ensure their findings stand up to scrutiny? The answer lies in strategic test selection during the planning phase—a process that shapes outcomes before data collection begins.

Study Design and Hypothesis Formulation

A clear hypothesis acts as a compass. It determines whether analysts need to compare groups, measure relationships, or predict outcomes. Consider these three pillars when matching methods to goals:

| Criteria | Impact on Selection | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Variables Count | Single vs. multi-variable tests | Blood pressure vs. diet/exercise effects |

| Data Type | Continuous vs. categorical tools | Weight measurements vs. survey responses |

| Study Structure | Paired vs. independent approaches | Pre/post treatment analysis |

Paired vs. Unpaired Comparisons

Repeated measurements from the same subjects—like tracking cholesterol levels before and after medication—require paired tests. These account for individual variations that could skew results.

Independent groups, such as comparing two different medications across separate patient cohorts, demand unpaired methods. Tools like this statistical test selector help navigate these distinctions efficiently.

Choosing upfront prevents bias—like avoiding the temptation to switch tests after seeing initial numbers. Whether evaluating drug efficacy or market trends, this disciplined approach turns raw observations into trustworthy evidence.

Statistical Tests for Comparing Groups

What separates breakthrough discoveries from flawed conclusions in experimental research? Often, it’s the precision of group comparison techniques that determines whether findings hold scientific merit.

Assessing Two-Group Comparisons

When analyzing two groups, researchers choose between parametric and distribution-free methods. The t-test excels with normally distributed data, while the Mann-Whitney U test handles skewed distributions. Consider a clinical trial comparing blood pressure reduction between medications:

| Test Type | Data Requirement | Clinical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Parametric | Normal distribution | Unpaired t-test for drug A vs. B |

| Nonparametric | No distribution assumptions | Mann-Whitney for pain score rankings |

Megahed’s ventilator study demonstrated proper application—using t-tests for normal lab values and Mann-Whitney for skewed symptom scores. This dual approach maintains accuracy across data types.

Analyzing Multiple Groups

Comparing three or more groups requires strategic methods to avoid error inflation. A common mistake involves running multiple t-tests, which increases false positive risks by 35% in typical studies. The solution? Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc testing.

Chowhan’s fluid responsiveness research showcased this effectively. Instead of comparing three treatments pairwise, they used ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. This preserves statistical power while identifying specific differences between groups.

Proper technique selection transforms raw observations into trustworthy evidence. Whether evaluating medical interventions or behavioral patterns, these methods help researchers draw valid conclusions about treatment impacts and population differences.

Statistical Tests for Paired Data

When measuring treatment effects or tracking biological changes, paired analysis offers unmatched precision. This approach compares measurements from the same subjects under different conditions—like blood pressure readings before and after medication. By focusing on individual differences, it eliminates variability between separate groups.

Maximizing Accuracy in Repeated Measurements

Paired designs act as natural error-reducers. Consider a study tracking osteoarthritis patients’ pain levels during two therapies. Using each person as their own control accounts for unique biological factors that independent group comparisons might miss.

| Test Type | Data Requirements | Clinical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Paired t-test | Normally distributed continuous variables | LVOTVTI measurements before/after leg raises |

| Wilcoxon Signed-Rank | Non-normal or ordinal data | Heart rate changes post-COVID physiotherapy |

Chowhan’s fluid responsiveness research demonstrates proper application. By using paired t-tests for normally distributed cardiac parameters, they achieved precise results. Similarly, Verma’s team applied Wilcoxon tests to skewed heart rate data—ensuring validity without distribution assumptions.

These methods excel in scenarios like:

- Pre/post intervention studies

- Bilateral anatomical comparisons

- Sequential treatment evaluations

For continuous variables meeting normality criteria, our paired t-test guide details implementation steps. Nonparametric alternatives remain essential when data violates assumptions—proving that smart design often beats larger sample sizes.

Statistical Tests for Categorical Data Analysis

Categorical insights shape medical breakthroughs and policy decisions alike. These discrete classifications—like patient outcomes or demographic groups—require specialized analytical approaches to reveal hidden connections.

The chi-square test for independence examines relationships between two categorical variables. Imagine comparing vaccine efficacy across age brackets or treatment responses between genders. This method identifies whether observed patterns differ significantly from random chance.

For assessing how well observed data matches theoretical expectations, the chi-square goodness of fit test shines. Researchers might use it to verify if survey responses align with population demographics or if genetic traits follow predicted ratios.

| Test | Sample Size | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fisher’s Exact | <5 per cell | Rare disease subtype analysis |

| McNemar’s | Paired measurements | Pre/post therapy status changes |

Small sample scenarios demand precision. Fisher’s exact test calculates exact probabilities when expected frequencies fall below chi-square requirements—critical for early-stage clinical trials with limited participants.

McNemar’s test tackles paired categorical data, like tracking individual patients’ condition improvements after interventions. This approach maintains accuracy in longitudinal studies where subjects serve as their own controls.

Proper contingency table construction remains vital. Cross-tabulating variables reveals actionable patterns—whether evaluating medication success rates or public health campaign impacts. By mastering these tools, researchers transform simple yes/no observations into evidence-backed conclusions.

The Role of Parametric and Nonparametric Tests

Imagine two detectives solving the same case—one uses precise forensic tools, while the other relies on observational skills. This mirrors how parametric and nonparametric methods approach data analysis. Each strategy reveals truths, but their effectiveness depends on the evidence at hand.

When Precision Meets Perfect Conditions

Parametric tests thrive when three stars align: normally distributed variables, consistent variance across groups, and continuous measurements. Think drug trials tracking blood pressure changes—the classic bell curve pattern allows t-tests to detect subtle treatment effects. These methods offer maximum sensitivity, like a microscope finding cellular differences invisible to the naked eye.

Embracing Flexibility in Complex Scenarios

Nonparametric alternatives shine when data breaks the rules. Customer satisfaction surveys (ordinal rankings) or skewed income datasets demand distribution-free approaches. The Wilcoxon test handles messy variables without assumptions, acting as a Swiss Army knife for unconventional patterns. Though less powerful in ideal conditions, they prevent false conclusions when real-world data misbehaves.

Researchers face this crossroads daily. A vaccine study with 10,000 participants? Parametric methods capitalize on large, clean datasets. Analyzing emergency room wait times with outliers? Nonparametric tools preserve accuracy. The choice ultimately determines whether findings withstand scrutiny—or crumble under peer review.

FAQ

How do I choose between parametric and nonparametric tests?

Parametric tests like t-tests or ANOVA assume normally distributed data and equal variances. Use them when these conditions are met. Nonparametric alternatives like Wilcoxon or Mann-Whitney U are better for skewed distributions, small samples, or ordinal data.

What test compares three or more groups with continuous data?

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is ideal for comparing multiple groups. If results show significant differences, post-hoc tests like Tukey’s HSD identify which specific pairs differ. For non-normal data, consider the Kruskal-Wallis test.

When should I use a chi-square test?

Chi-square tests evaluate relationships between categorical variables, like comparing observed vs. expected frequencies. Use it for contingency tables—for example, testing if medication effectiveness differs between age groups using nominal or ordinal data.

What’s the advantage of paired tests over unpaired methods?

Paired tests (e.g., paired t-test, Wilcoxon signed-rank) reduce variability by analyzing matched observations—like pre- and post-treatment measurements. This increases sensitivity to detect true effects compared to unpaired approaches.

How does sample size impact test selection?

Larger samples (n > 30) often justify parametric tests due to the Central Limit Theorem. Smaller samples may require nonparametric methods. Power analysis helps determine adequate sample sizes to avoid Type II errors.

Can I use correlation analysis for categorical variables?

Pearson’s correlation works for continuous data. For categorical variables, use Cramer’s V (nominal) or Spearman’s rank (ordinal). Phi coefficient is suitable for 2×2 binary tables.

What if my data violates normality assumptions?

Transform data using log or square-root methods first. If violations persist, switch to nonparametric equivalents—like Mann-Whitney U instead of independent t-tests or Friedman test instead of repeated-measures ANOVA.