Modern enterprises make critical choices using mathematical frameworks most professionals never see. Behind every quality control system, risk assessment tool, and operational optimization strategy lies a pair of powerful probability models governing binary outcomes and rare events.

These statistical workhorses enable analysts to predict customer behavior patterns, forecast equipment failures, and optimize supply chains with mathematical precision. From healthcare diagnostics to financial forecasting, their applications span industries where accuracy determines success.

One model excels at calculating exact event probabilities in fixed trials, while the other shines in scenarios with vast potential occurrences. Together, they form an indispensable toolkit for converting raw data into actionable intelligence.

This guide demystifies their core principles through real-world examples. Readers will discover how tech giants use these frameworks to predict server crashes, and how manufacturers apply them to minimize product defects. The strategic advantage lies in knowing which model fits specific scenarios – a decision that separates adequate analysis from transformative insights.

Key Takeaways

- Master foundational concepts behind discrete event prediction models

- Identify practical applications across industries like tech and healthcare

- Learn to choose the right framework for binary vs. open-ended scenarios

- Develop skills to quantify uncertainty in business decisions

- Gain tools for improving quality control and risk management systems

- Understand how these models drive modern predictive analytics

Introduction

Every business decision carries inherent uncertainty – but modern tools turn guesswork into calculated strategy. At the core of this transformation lies the science of modeling event patterns through mathematical frameworks.

Statistical distributions act as blueprints for interpreting real-world phenomena. They reveal hidden structures in customer purchase records, equipment maintenance logs, and quality control reports. This analytical power transforms raw numbers into decision-ready intelligence.

Consider these applications across sectors:

- Predicting peak service demand in hospitality

- Calculating defect rates in production lines

- Estimating patient arrival rates at clinics

The true value emerges in quantifying unpredictability. Analysts create confidence intervals around forecasts – a 95% certainty that machine failures will stay below threshold X, or a 99% probability that customer wait times remain under Y seconds. This precision enables leaders to allocate resources strategically.

Mastering these models requires understanding their distinct strengths. One excels in fixed-scenario predictions, while another thrives in open-ended event tracking. We’ll explore how to match each tool to specific business challenges, ensuring optimal results from marketing campaigns to inventory management.

Foundations of Probability and Statistical Distributions

Decoding event patterns begins with mastering the building blocks of probability theory. These principles transform chaotic outcomes into quantifiable predictions using three core components: random variables that assign numerical values to events, probability mass functions mapping specific results, and cumulative distribution functions calculating outcome ranges.

Key Concepts and Terminology

Effective analysis requires fluency in foundational terms:

- Independence: Outcomes unaffected by previous results

- Identical distribution: Consistent probability parameters across trials

- Discrete variables: Countable outcomes like defect counts or survey responses

Understanding Bernoulli Trials

A single Bernoulli trial produces one of two results: success (p) or failure (1-p). Consider quality control checks where a machine either passes inspection (p=0.97) or requires maintenance. When repeated under identical conditions, these trials form the basis for calculating multi-event probabilities.

Real-world applications demand strict adherence to two rules: unchanging success rates across trials and outcome independence. Violating these assumptions – like worn machinery increasing failure probabilities over time – invalidates results. Proper experimental design ensures these models deliver reliable insights for decision-making.

Understanding Poisson and Binomial Distributions

Analysts face a critical choice when modeling discrete events: which probability framework delivers accurate predictions? Two models dominate this decision space—one designed for controlled experiments, the other for open-ended scenarios.

The binomial model thrives in structured environments with fixed trials. Quality inspectors use it to calculate defect probabilities in 100-unit batches. Marketing teams apply it to predict survey response rates. Its power comes from three constants: predetermined sample size, binary outcomes, and unchanging success probabilities.

Contrast this with the Poisson approach, engineered for counting sporadic incidents across continuous intervals. Hospital administrators track emergency room arrivals per hour. IT departments monitor server crashes weekly. This framework excels when tracking rare occurrences in vast populations.

“Choosing between these tools isn’t academic—it determines whether your risk assessments reflect reality.”

| Factor | Binomial | Poisson |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Fixed (n) | Unbounded |

| Event Probability | Constant (p) | Varies (λ) |

| Ideal Use Case | Pass/fail testing | Rare event tracking |

| Key Metric | Success count | Events per unit |

Manufacturers demonstrate this distinction clearly. When checking 500 widgets for defects, the binomial formula provides exact failure probabilities. But when estimating production line stoppages over six months, the Poisson method captures the unpredictable nature of mechanical failures.

Strategic model selection impacts every phase of analysis—from initial data collection to final confidence intervals. Financial institutions using the correct framework reduce forecasting errors by 18-22% according to recent studies. The right choice transforms raw counts into actionable intelligence.

Exploring the Binomial Distribution

At the heart of discrete event analysis lies a powerful formula for calculating exact probabilities. This framework enables professionals to quantify outcomes in scenarios with fixed trials and binary results – from product defect checks to clinical trial success rates.

Probability Mass Function and Cumulative Functions

The probability mass function (PMF) acts as the mathematical engine for binomial calculations. For n independent trials with success probability p, it determines the likelihood of observing exactly k successes using the formula:

P(X = k) = C(n,k) × pk × (1-p)n-k

This equation combines combinatorial counting with probability scaling. The binomial coefficient C(n,k) represents the number of ways to achieve k successes in a sample – crucial for applications like A/B testing or manufacturing defect analysis.

Cumulative distribution functions expand this capability to ranges. Quality managers might calculate the probability of ≤3 defective units in a 500-item batch. Financial analysts could determine the chance of ≥8 successful trades in 10 attempts. These calculations transform raw data into risk assessments.

Key metrics like expected value (np) and variance (np(1-p)) offer immediate insights. A customer service center handling 200 daily calls with a 75% resolution rate can predict 150 successful outcomes daily. Variance quantifies potential fluctuations – essential for resource planning.

Strategic adjustments become measurable through these formulas. Increasing sample size narrows outcome variability, while shifting p alters success probabilities. For detailed implementation strategies, explore real-world applications in operational analytics.

Examining the Poisson Distribution

Healthcare planners faced a critical challenge in 2004 – optimizing organ transplant logistics across Britain. Researchers analyzed 1,330 donations over 730 days, revealing an average of 1.82 life-saving procedures daily. This discovery became a blueprint for modeling unpredictable occurrences through mathematical frameworks.

The formula P(r) = (λr/r!) × e-λ transforms raw data into actionable forecasts. Here, λ represents average event frequency – like 1.82 daily transplants. This calculation method helps professionals anticipate scenarios ranging from zero occurrences to statistical outliers.

Event Rates in Operational Strategy

Modern organizations leverage these principles across industries:

- Tech firms predict server downtime using historical crash data

- Retailers optimize staffing based on projected customer arrivals

- Manufacturers anticipate machinery failures through maintenance logs

The UK medical study demonstrates practical implementation. With 1.82 as the daily rate, planners calculated exact probabilities for various donation scenarios. This approach informed resource allocation for surgical teams and organ preservation systems.

Financial analysts apply similar logic when modeling loan defaults. Insurance firms use it to assess claim frequencies. The model’s strength lies in handling situations where individual probabilities are minuscule, but potential occurrences are vast – a concept explored in discrete event modeling frameworks.

Event rate analysis creates strategic advantages. Operations managers reduce overstocking costs by 23-31% through demand forecasting. Quality teams detect anomalies when actual defect counts diverge from predicted ranges. This mathematical approach turns uncertainty into measurable risk.

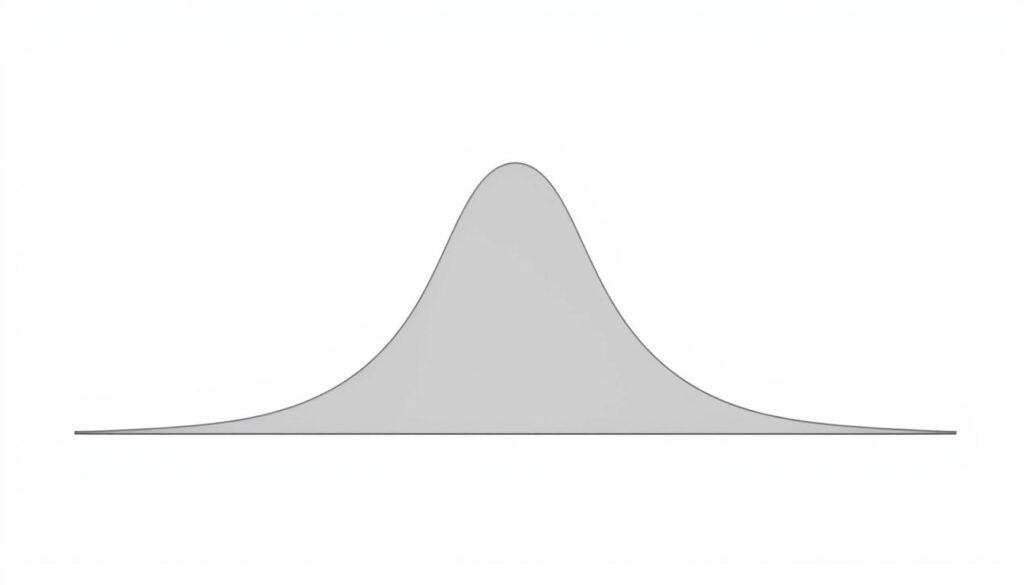

The Normal Distribution: Role and Relevance

From classroom test scores to galaxy sizes, the bell curve appears wherever variation follows predictable patterns. This universal shape forms the backbone of statistical analysis through two defining parameters: μ (mean) and σ (standard deviation). Together, they create a symmetrical model where 95% of values fall within 1.96 standard deviations of the average.

Normal Approximation in Statistical Analysis

Analysts simplify complex calculations using normal approximations when working with large datasets. For binomial scenarios, this method becomes reliable when:

- Sample sizes exceed 5 observations

- Absolute skewness stays below 0.3

- Event probabilities show minimal fluctuation

Financial institutions demonstrate this principle effectively. When assessing loan default risks across 10,000 applications, the normal model predicts outcomes faster than exact binomial calculations – without sacrificing accuracy.

Estimating Confidence Intervals

The 95% confidence rule (μ ± 1.96σ) transforms raw data into decision-making tools. Pharmaceutical researchers use this range to determine drug efficacy margins. Manufacturers apply it to set quality control thresholds, knowing 19/20 products will meet specifications.

“Approximation isn’t about cutting corners – it’s about focusing resources where precision matters most.”

| Approximation Factor | Requirement | Business Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | n > 5 | Reduces computational costs |

| Skewness Limit | |γ| | Ensures valid comparisons |

| Data Type | Continuous metrics | Simplifies trend analysis |

Central Limit Theorem applications make these techniques indispensable. Even non-normal data becomes analyzable through sample means, enabling robust insights from marketing surveys to clinical trials. Strategic use of approximation criteria prevents skewed interpretations while maintaining analytical agility.

Comparative Analysis: Binomial vs. Poisson Distribution

Selecting the right analytical tool separates precise forecasts from flawed predictions in data-driven industries. Two frameworks dominate event modeling—one built for controlled experiments, the other for unpredictable scenarios. Understanding their boundaries prevents costly misinterpretations of customer behavior patterns or equipment failure rates.

The fixed-trial model thrives when testing 500 products for defects or predicting survey response rates. Its strength lies in predefined sample sizes and consistent success probabilities. Contrast this with the rate-based approach, designed for tracking infrequent incidents like network outages or emergency room visits.

| Decision Factor | Fixed-Trial Framework | Rate-Based Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Trials | Defined batch size | Open-ended observation |

| Key Metric | Success count | Events per unit |

| Approximation Threshold | n ≥ 20, p ≤ 0.05 | λ = np ≤ 1 |

Convergence occurs when expanding sample sizes meet shrinking success probabilities. Telecom companies use this principle to estimate call center errors across millions of interactions—switching calculations from complex combinatorial math to simpler exponential functions.

Three rules guide effective approximation:

- Sample sizes exceeding 50 units

- Success probabilities below 10%

- Product of trials and probability under 1

Manufacturers applying these criteria reduce computation time by 40% when monitoring rare defects in mass production. The strategic choice between models directly impacts resource allocation and risk assessment accuracy across industries.

Modeling Successes: From Trials to Scores

Industries measure progress through quantifiable outcomes—every success tells a story. Translating raw trial data into actionable scores requires precise frameworks that balance mathematical rigor with practical relevance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FwIguCYyu7o

Interpreting Successes in Data

Defining meaningful outcomes separates useful analysis from noise. Clinical researchers might count recovered patients, while manufacturers track defect-free products. Consistency matters: a success in one trial must equal a success in all others.

Consider drug testing. If 75 of 100 patients improve, the sample proportion (p=0.75) estimates the true population success rate. This mirrors how averages summarize continuous data—but with binary outcomes.

Applying the Binomial Formula

The formula p = r/n transforms counts into probabilities. For 200 treated patients with 150 recoveries:

| Component | Value | Business Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Successful trials (r) | 150 | Quantifies effectiveness |

| Total trials (n) | 200 | Determines sample reliability |

| Success rate (p) | 0.75 | Guides scaling decisions |

This approach powers quality control systems. A factory testing 500 units calculates defect probabilities using the same binomial distribution principles. Confidence intervals around estimates reveal precision levels—critical for regulatory submissions.

“Success metrics only matter when tied to strategic goals. Our models must reflect real-world decision parameters.”

From clinical research to production lines, consistent success definitions enable comparisons across trials and time periods. The mathematical framework adapts to any scenario with fixed number of successes and clear outcome boundaries.

Applications in Medical Statistics and Psychometrics

Healthcare decisions and psychological assessments rely on precise interpretation of numerical patterns. Statistical models transform raw measurements into diagnostic tools and evaluation frameworks, creating actionable benchmarks for professionals.

Medical Test Analysis and Reference Ranges

Newborn weight data from 3,226 infants reveals a classic bell curve pattern. With mean 3.39kg and standard deviation 0.55kg, 95% of healthy babies fall between 2.31kg and 4.47kg. This reference range helps clinicians identify at-risk infants using WHO thresholds: under 2.5kg signals potential complications, while over 4kg requires monitoring.

Item Response Theory and Score Distributions

Modern testing systems employ advanced models to evaluate question performance. These frameworks analyze how respondents interact with assessment items, mapping success probabilities to skill levels. The approach ensures test results reflect true ability rather than random guessing.

Both fields demonstrate how distribution analysis turns abstract numbers into life-changing insights. From neonatal care to educational assessments, these applications prove that strategic data interpretation remains healthcare’s unsung hero.

FAQ

When should I use the binomial distribution instead of the Poisson?

The binomial distribution models scenarios with a fixed number of independent trials, each having two outcomes (success/failure). Use it when you know the exact sample size and probability of success. The Poisson distribution suits rare events over continuous intervals—like call center arrivals—where the exact number of trials isn’t predefined.

How does the normal approximation apply to the binomial distribution?

When sample sizes are large and probabilities aren’t extreme (e.g., np ≥ 10), the normal distribution approximates binomial probabilities. This simplifies calculations for confidence intervals or hypothesis tests while maintaining accuracy. Always verify the 10% rule—sample size ≤ 10% of the population—to ensure independence.

What distinguishes the binomial and Poisson distributions in real-world analysis?

The binomial distribution counts successes in fixed trials (e.g., defective items in a batch), while the Poisson measures event frequency over time/space (e.g., website visits per hour). The binomial requires known parameters (n, p), whereas Poisson relies on an average rate (λ) without a fixed upper limit.

When is the Poisson distribution a better fit than the binomial?

Choose Poisson when events are infrequent, occur independently, and the exact number of opportunities isn’t measurable. Examples include modeling accidents at an intersection or system failures. It’s ideal for low-probability scenarios where the binomial’s fixed-trial framework feels restrictive.

Why are Bernoulli trials critical to understanding the binomial distribution?

Bernoulli trials—single experiments with binary outcomes—form the foundation of the binomial model. Each trial’s independence and consistent success probability allow the binomial formula to scale results across multiple attempts, such as predicting the likelihood of 8 heads in 10 coin flips.

How do these distributions apply to medical statistics?

The binomial distribution evaluates diagnostic test accuracy (e.g., true positives in a patient cohort), while Poisson models rare adverse events in clinical trials. Normal approximations help establish reference ranges for lab results, ensuring 95% of healthy populations fall within defined thresholds.