Statistical analysis errors derail nearly 7 in 10 studies examining relationships between variables – often because researchers select analytical tools before understanding their data’s true nature. This foundational misstep creates ripple effects, from skewed conclusions to challenges reproducing results.

Modern researchers face a pivotal crossroads: choosing between methodologies that assume specific data patterns versus those adapting to raw information. This decision determines whether findings withstand scrutiny or crumble under peer review. A comprehensive guide from leading institutions reveals how strategic test selection boosts credibility across industries.

Three factors separate impactful studies from forgettable ones:

1. Explicit alignment between hypotheses and analytical frameworks

2. Rigorous evaluation of data distribution before test selection

3. Clear differentiation between exploratory analysis and confirmatory research

Mastering these principles transforms statistical approaches from technical requirements into strategic assets. Professionals who navigate this landscape skillfully produce work that shapes policies, drives innovation, and withstands evolving academic standards.

Key Takeaways

- Hypothesis clarity dictates appropriate analytical methodologies

- Confirmatory research demands stricter statistical protocols than exploratory analysis

- Data distribution characteristics directly influence test selection validity

- Strategic methodology choices enhance research reproducibility and impact

- Understanding both analytical approaches expands problem-solving capabilities

Introduction to Statistical Testing

At the core of impactful studies lies a critical foundation: aligning research questions with appropriate verification methods. This alignment determines whether findings withstand scrutiny or collapse under methodological flaws.

Blueprint for Reliable Analysis

Every investigation starts with hypothesis formulation. Confirmatory hypotheses require strict protocols – like predetermined variables and rigid test selection. Exploratory approaches allow more flexibility but demand transparent reporting of data patterns.

Study design dictates analytical paths. Consider a medical trial comparing treatments across matched patient groups. Using standard t-tests here would violate independence assumptions, as participants share demographic characteristics. Proper analysis requires paired comparison methods instead.

| Study Design | Data Type | Common Tests | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crossover Trial | Paired | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank | Within-subject comparisons |

| Case-Control | Matched | McNemar’s Test | Dependency adjustments |

| Independent Samples | Unrelated | Mann-Whitney U | No participant overlap |

Strategic Methodology Selection

Three questions guide test selection:

- Does the design involve repeated measurements?

- What distribution characteristics does the data show?

- Are we confirming relationships or exploring patterns?

Clinical researchers analyzing pre/post treatment effects often make this error: applying independent sample tests to inherently linked data points. Such missteps produce misleading p-values that overstate significance.

Professional teams implement validation checklists before analysis. These ensure methodological choices reflect both study objectives and data realities – crucial for maintaining scientific integrity while extracting meaningful information.

Understanding Parametric Testing

Parametric analysis unlocks precise conclusions when data meets strict distribution criteria. These methods derive their strength from predefined population parameters, offering robust frameworks for hypothesis verification. Proper application requires alignment between data characteristics and methodological requirements—a balance that separates reliable findings from questionable results.

Assumptions and Data Requirements

Parametric techniques demand verification of three core conditions: normality in distribution, homogeneity of variance, and interval-level measurement. The normal distribution assumption often receives primary attention, as skewed data fundamentally alters test validity. Researchers typically assess this through graphical methods (Q-Q plots) or statistical checks like the Shapiro-Wilk test.

When assumptions hold, these methods provide unparalleled advantages. Confidence intervals for population parameters and precise effect size estimates become possible—features particularly valuable in clinical trials and psychological studies. “Parametric approaches transform raw data into actionable insights when their strict requirements are met,” notes a biostatistics researcher from Johns Hopkins University.

Common Parametric Tests and Their Applications

| Test | Application | Data Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Independent t-test | Comparing means between two unrelated groups | Normal distribution in each group |

| Pearson’s r | Measuring linear relationships | Both variables normally distributed |

| ANOVA | Comparing three+ group means | Normality and equal variances |

These tools excel in controlled experimental settings. Pharmaceutical researchers use ANOVA to compare drug efficacy across dosage groups while accounting for baseline characteristics through covariate adjustments. The key lies in rigorous pre-test diagnostics—ensuring data alignment with methodological prerequisites before drawing conclusions.

Exploring Non-Parametric Testing

Modern research often encounters data that defies textbook assumptions. This reality demands analytical tools capable of adapting to real-world irregularities while maintaining scientific rigor.

Key Characteristics and Benefits

Distribution-free methods thrive where traditional approaches falter. They analyze small sample sizes and ordinal measurements without requiring normally distributed data. A biostatistician from UCLA notes: “These techniques preserve validity when data behaves unpredictably – a common scenario in field studies.”

| Test | Use Case | Data Type |

|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon Signed-Rank | Paired measurements | Ordinal/Continuous |

| Mann-Whitney U | Independent groups | Non-normal distribution |

| Spearman’s Rho | Monotonic relationships | Rank-based data |

When to Use Non-Parametric Procedures

Three scenarios demand these methods:

- Data fails normality checks through Q-Q plots or Shapiro-Wilk tests

- Studies involve ranking systems or Likert scales

- Sample sizes below 30 participants per group

Examples in Practical Research Scenarios

Market researchers frequently apply these techniques when analyzing customer satisfaction surveys. The Mann-Whitney U test compares product ratings between demographic groups, while Spearman correlations reveal hidden patterns in preference rankings.

Clinical trials with skewed recovery times use Wilcoxon tests to assess treatment effects. This approach maintains analytical integrity when continuous data doesn’t follow normal patterns – a frequent occurrence in real-world medical data.

Parametric and Non-Parametric Tests: Comparative Insights

Choosing between analytical approaches shapes research validity from the ground up. These methodologies differ in their mathematical foundations, interpretive potential, and real-world applicability—factors demanding careful evaluation before implementation.

Differences in Data Assumptions and Distribution

Traditional methods require data to follow normal distribution patterns, while their counterparts operate without strict shape requirements. This distinction becomes critical when analyzing skewed datasets or ordinal measurements like survey rankings.

A common misunderstanding surrounds the Mann-Whitney U test. Many assume it compares medians, but identical medians can still yield significant results. Only when groups share distribution shapes does the test reliably indicate location shifts affecting both means and medians equally.

Statistical Power and Flexibility in Analysis

When assumptions hold, traditional approaches detect smaller effect sizes with greater precision. Their mathematical models calculate exact probabilities, making them ideal for controlled experiments. Distribution-free methods trade some power for adaptability in complex real-world scenarios.

Consider clinical data with irregular measurement intervals. Non-parametric techniques can identify treatment effects that standard t-tests might miss due to violated assumptions. This flexibility comes at a cost—reduced sensitivity to subtle differences that parametric models would capture.

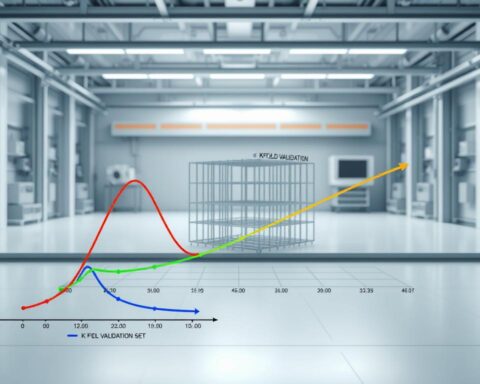

Practical Applications in Research Data Analysis

Real-world data challenges demand more than textbook solutions—they require strategic analytical choices. Consider a clinical study examining leg ulcer treatments across 20 patients with 30 total ulcers. Here lies a critical lesson: multiple measurements per subject don’t equal independent data points.

Case Studies Illustrating Test Selection

The leg ulcer study reveals why understanding data structure matters. While 30 ulcers suggest ample observations, patient health status creates correlations between wounds on the same individual. True independent samples number 20—not 30. This distinction determines whether results reflect biological reality or statistical artifacts.

| Scenario | Data Challenge | Appropriate Test |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple ulcers per patient | Correlated observations | Paired t-test |

| Treatment comparison | Normal distribution | Independent t-test |

| Ordinal satisfaction scores | Non-normal data | Mann-Whitney U |

Tailoring Testing Methods to Research Needs

Clinical trials frequently demonstrate this principle. When comparing two treatment groups with normally distributed outcomes, researchers employ standard t-tests. However, studies using Likert scales or ranked preferences often require distribution-free alternatives.

Social science research offers parallel insights. A survey comparing income brackets across demographic groups might use ANOVA for parametric analysis. But skewed economic data could necessitate Kruskal-Wallis testing instead. The healthknowledge.org.uk guide provides expanded frameworks for these decisions.

Three rules govern effective method selection:

- Identify the true unit of analysis

- Verify distribution characteristics

- Match test assumptions to data reality

These principles apply universally—from pharmaceutical trials to market research. By aligning methods with design, professionals ensure their results withstand scrutiny while revealing actionable patterns.

Guidelines for Choosing the Appropriate Test

Effective analysis hinges on matching methodology to data realities. Researchers must navigate three core considerations: measurement types, distribution patterns, and practical limitations. This systematic approach transforms raw information into credible conclusions.

Data Characteristics Drive Decisions

Start by classifying variables – nominal categories require different tools than interval measurements. For multi-group comparisons, analysis of variance suits normal distributions, while Kruskal-Wallis handles ordinal or skewed data. Sample size thresholds matter: recent guidelines show parametric methods work with non-normal data when groups exceed 15-20 observations.

Power Versus Practicality Balance

Traditional methods offer precision with perfect assumptions, but real-world studies often need adaptable solutions. Small samples or censored data demand distribution-free techniques. Prioritize transparency: document all checks for normality and variance homogeneity before finalizing choices.

Create decision matrices listing variables, group counts, and distribution status. This visual mapping prevents analytical mismatches. Remember – no single approach fits all scenarios. Master researchers combine statistical rigor with situational awareness to select tools that reveal truths without distorting reality.

FAQ

What are the primary indicators that a non-parametric test should be used?

Non-parametric tests are ideal when data isn’t normally distributed, sample sizes are small (often below 30), or the study involves ordinal/categorical variables. They’re also preferred when outliers skew results or assumptions like homogeneity of variance aren’t met.

How does violating parametric test assumptions impact results?

Violating assumptions—such as normality, equal variance, or interval data—can lead to inaccurate p-values and inflated Type I/II errors. For example, using a t-test on skewed data might falsely detect differences. Always validate assumptions before choosing parametric methods.

Can you name real-world scenarios where non-parametric tests excel?

Non-parametric tests shine in fields like customer satisfaction surveys (ordinal ratings), medical research with small patient cohorts, or ecological studies measuring non-linear trends. The Mann-Whitney U test, for instance, effectively compares skewed income data between groups.

Why might larger sample sizes sometimes justify parametric tests?

Central Limit Theorem suggests that with larger samples (typically n > 30), means approximate normality even if raw data doesn’t. This allows parametric tests like ANOVA or t-tests to deliver reliable results despite minor deviations from distributional assumptions.

What’s the trade-off between statistical power and test flexibility?

Parametric tests often have higher power to detect true effects when assumptions hold, but they’re less flexible. Non-parametric methods sacrifice some power for adaptability, making them safer for complex or unpredictable data structures common in exploratory research.

How do researchers assess normality before selecting a test?

Tools like Shapiro-Wilk tests, Q-Q plots, or Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests evaluate normality. However, visual inspection and understanding the data’s context—like known skew in biological measurements—are equally critical. Robustness checks ensure test choices align with the data’s behavior.

When comparing two groups, what alternatives exist if a t-test isn’t suitable?

The Mann-Whitney U test (for independent groups) or Wilcoxon signed-rank test (for paired data) are robust non-parametric alternatives. These compare medians instead of means and handle outliers or non-normal distributions effectively.