In 2005, global income disparity reached a staggering 61-68% concentration among populations – enough wealth to end extreme poverty seven times over. This revelation underscores why quantifying resource distribution remains critical for addressing systemic challenges. Developed by Italian scholar Corrado Gini in 1912, a pioneering statistical tool transformed how societies visualize economic divides.

The metric scales from 0 (total equality) to 1 (maximum imbalance), acting as a powerful lens for examining wealth patterns. OECD nations demonstrate its practical value: post-tax income measurements show Slovakia at 0.24 and Mexico at 0.49. These figures reveal how policy decisions directly shape societal outcomes.

Modern professionals leverage this analytical framework to convert raw data into strategic advantages. From evaluating pirate crews’ loot divisions to assessing Silicon Valley’s wage gaps, the approach provides universal insights. Its applications stretch beyond economics into healthcare access, education funding, and housing policies.

Mastering this measurement unlocks three transformative capabilities: identifying hidden imbalance drivers, testing intervention effectiveness, and forecasting long-term trends. Organizations like the World Bank and Fortune 500 companies now integrate these insights into decision-making processes, proving its adaptability across sectors.

Key Takeaways

- A century-old statistical model remains central to modern economic evaluations

- Scale ranges from perfect balance (0) to total concentration (1) of resources

- Real-world applications span historical cases to contemporary policy debates

- OECD comparisons demonstrate measurable impacts of taxation systems

- Strategic analysis informs solutions for healthcare, education, and wage gaps

Introduction to Income Inequality and the Gini Coefficient

Over 115 studies have explored how economic disparities influence public health outcomes – yet researchers still debate their exact relationship. This ongoing discussion reveals a critical truth: how we measure disparities shapes our understanding of their effects on societies.

Overview of Income Distribution

Economic disparity extends beyond bank account balances. It weaves through education access, healthcare quality, and neighborhood resources, creating patterns that affect entire communities. Sophisticated analytical tools help decode these complex interactions between policy decisions and lived experiences.

Relevance in Economic and Public Health Contexts

Public health research uncovers startling connections: regions with uneven income distribution metrics often show higher rates of chronic disease and lower life expectancy. A 2023 analysis found that using different inequality measures could reverse conclusions about healthcare access – proving tool selection matters.

Key insights emerge:

- Economic structures influence mental health outcomes as strongly as physical health indicators

- Infant mortality rates correlate more closely with relative poverty levels than absolute income figures

- Policy interventions require data that captures both individual circumstances and systemic patterns

Historical Background and Development

Modern economic analysis owes much to early 20th-century innovators who transformed abstract ideas into practical tools. At the heart of this transformation lies a statistical breakthrough that reshaped how societies quantify resource allocation patterns.

Corrado Gini’s Contributions

Italian statistician Corrado Gini bridged mathematics and social science in his 1912 paper Variabilità e mutabilità. His work focused on measuring variability – not just in economics, but across biological and demographic studies. This interdisciplinary approach led to a groundbreaking method for assessing wealth concentration.

Gini’s key insight involved comparing actual resource distribution to perfect equality. His numerical index – calculated from the area between two curves – provided clearer comparisons than previous visual methods. By 1915, mathematician Gaetano Pietra solidified this concept through geometric interpretations still used today.

Evolution from the Lorenz Curve Framework

American economist Max Lorenz laid crucial groundwork in 1905 with his graphical representation of wealth distribution. Gini’s innovation transformed these visual comparisons into precise numerical values, enabling cross-regional analysis and policy evaluations.

The 1970s marked a turning point when Canada became the first nation to adopt this measure in official statistics. Their income distribution data showed consistent scores between 0.28 and 0.30 – tangible proof of the tool’s real-world applicability. This institutional adoption paved the way for global use in assessing economic systems and social programs.

Fundamental Concepts Behind the Gini Coefficient

Decoding economic equity involves both visual patterns and precise calculations. At its core lies a graphical tool that maps resource allocation against an ideal benchmark. This pairing transforms abstract data into actionable insights for policymakers and analysts.

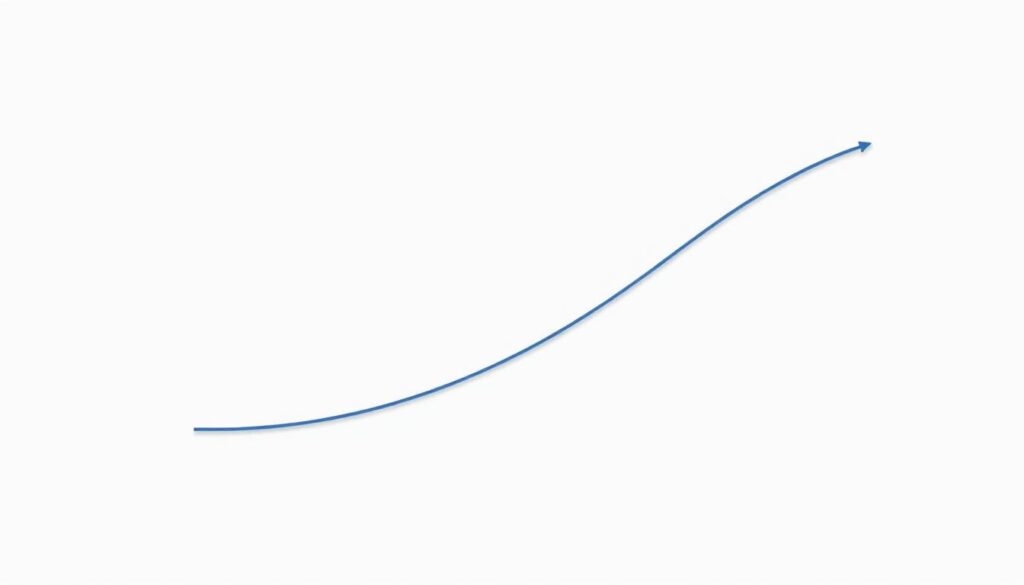

Understanding the Visual Foundation

The Lorenz curve plots cumulative population percentages against their share of total income. In a perfectly balanced system, the bottom 40% would control 40% of resources – forming a straight diagonal line. Real-world distributions create curves that bow beneath this equality benchmark.

Translating Patterns Into Numbers

The metric’s calculation compares the area between actual distribution and perfect balance. Values range from 0 (complete parity) to 1 (total concentration). Most nations fall between 0.25 and 0.60 on this scale, as shown in recent comparisons:

| Value Range | Distribution Type | Example Economy |

|---|---|---|

| 0.20-0.29 | High equality | Nordic countries |

| 0.30-0.39 | Moderate disparity | Canada, Germany |

| 0.40+ | Significant inequality | United States, China |

This statistical measure also relates to average income differences across population pairs. Analysts use it to compare regions and track changes over time – like monitoring how tax reforms affect wealth distribution patterns.

Exploring the Gini Coefficient for Inequality Analysis

Three crewmates splitting treasure – 12, 4, and 2 gold coins – face dramatically different outcomes than three equal shares. This simple scenario demonstrates how analysts quantify resource allocation patterns through systematic calculation. By comparing all possible income pairs and averaging differences, they create a ratio that reveals distribution fairness.

Calculation Methods and Practical Examples

Using the three-person case:

- Total differences: |12-4| + |12-2| + |4-2| = 18

- Average difference: 18 ÷ 3 pairs = 6

- Mean income: (12+4+2) ÷ 3 = 6

The final calculation: 6 ÷ (2×6) = 0.5. This shows moderate imbalance – neither perfect equality nor total concentration.

Role in Assessing Economic Disparities

Historical records reveal striking contrasts. Pirate crews like the Royal Rover maintained near-equal shares (0.06 score), while British naval ships allocated four times more pay to officers than sailors. Modern applications extend these principles, as shown in recent policy evaluations of tax systems.

Organizations now use this approach to track housing affordability gaps and healthcare access patterns. By converting complex data into clear metrics, decision-makers identify which interventions actually reduce disparities – and which merely shift resources between groups.

Alternative Measures of Income Inequality

When a single metric can’t capture complex economic patterns, analysts turn to specialized tools. These alternatives address specific gaps in traditional methods, offering tailored solutions for modern policy challenges.

The Atkinson Index and Sensitivity Parameters

Imagine two cities with identical average incomes – but different distribution patterns. The Atkinson Index helps determine which community achieves higher social welfare. Its secret weapon? A customizable sensitivity parameter (ε) that prioritizes either:

- Broad-based prosperity (ε=0.5)

- Urgent poverty reduction (ε=2)

Higher ε values spotlight lower-income groups. An Atkinson score of 0.20 reveals a striking insight: society could maintain current welfare levels with just 80% of total income – if distributed equally.

| ε Value | Policy Focus | Sample Application |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Moderate redistribution | EU social program evaluations |

| 1.0 | Standard welfare analysis | OECD country comparisons |

| 2.0 | Extreme poverty elimination | UN Sustainable Development Goals |

The Generalized Entropy Index and Its Applications

While Atkinson examines the bottom, GE indices track wealth concentration at the top. Their α parameter acts like a zoom lens:

- Negative α (-1): Magnifies low-income disparities

- Positive α (2): Highlights top 1% earnings

This flexibility makes GE measures indispensable for regional analysis. Researchers can separate urban-rural gaps from within-city variations – crucial for targeted interventions.

| GE Measure | Focus Area | Real-World Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GE(-1) | Basic needs access | African nutrition programs |

| GE(0) | General inequality | US Census Bureau reports |

| GE(2) | Elite wealth tracking | Forbes billionaire studies |

Modern analysts increasingly combine multiple measures. This layered approach reveals whether tax reforms primarily affect middle-class families or corporate executives – insights no single metric provides.

Advantages and Limitations of the Gini Coefficient

While widely used in economic assessments, this measurement tool reveals both strengths and blind spots. Its ability to condense complex distribution patterns into a single value makes it invaluable for quick comparisons. However, practitioners must recognize scenarios where its simplicity masks critical details.

Middle-Class Focus in Economic Measurements

The metric shows heightened responsiveness to changes among median earners. This proves useful when evaluating tax policies affecting broad populations. Yet it may overlook critical disparities at society’s extremes – where poverty lines or top-tier wealth accumulation demand attention.

When Curves Cross: Hidden Complexities

Identical scores can emerge from vastly different resource allocations. Imagine two regions: one with uniform middle-class earnings, another combining extreme wealth and poverty. Both might share the same coefficient value, requiring analysts to supplement data with graphical analysis for accurate interpretation.

These limitations don’t negate the tool’s utility but highlight the need for complementary approaches. Pairing numerical scores with localized studies creates a fuller picture of economic realities. Strategic thinkers use this awareness to design targeted interventions that address specific gaps in resource access.

FAQ

How does the Gini Coefficient measure income inequality?

The Gini Coefficient quantifies inequality by comparing a population’s income distribution to a perfectly equal standard. It uses the Lorenz Curve—a graphical tool—to calculate the ratio between the area of observed inequality and the maximum possible disparity. Values range from 0 (total equality) to 1 (extreme inequality), offering a snapshot of economic gaps.

What does a Gini value of 0.4 indicate about a country’s economy?

A Gini value of 0.4 suggests moderate inequality, often seen in mixed economies like the United States. For context, the U.S. scored 0.48 in 2022, reflecting wider disparities than nations like Sweden (0.29) but lower than Brazil (0.53). Policymakers use such thresholds to design tax reforms or social programs targeting wealth redistribution.

How is the Lorenz Curve used in calculating the Gini Coefficient?

The Lorenz Curve plots cumulative income shares against population percentiles. The Gini Coefficient derives from the area between this curve and the “perfect equality” line. A larger gap means higher inequality. For example, if the top 10% earn 50% of income, the curve bends sharply, increasing the Gini value.

Why might the Gini Coefficient overlook poverty levels in some analyses?

This metric focuses on relative disparities, not absolute deprivation. Two countries with identical Gini values could have vastly different poverty rates—one with widespread low incomes and another with a wealthy elite. Analysts often pair it with poverty indices to capture a fuller picture of economic health.

How do alternative measures like the Atkinson Index differ from the Gini approach?

The Atkinson Index incorporates societal tolerance for inequality through a sensitivity parameter, prioritizing reductions among lower-income groups. Unlike the Gini Coefficient—which treats all disparities equally—it allows policymakers to weigh ethical judgments about fairness into their evaluations.

What are the limitations of using the Gini Coefficient for policy decisions?

It can’t distinguish between overlapping Lorenz Curves, potentially masking nuanced shifts in middle-class dynamics. For instance, tax reforms might reduce inequality overall but leave the poorest groups unchanged—a detail the Gini value alone wouldn’t reveal. Combining it with decile analysis or poverty metrics strengthens insights.