Imagine discovering nearly half of medical breakthroughs never reach patients—not because of flawed theories, but improper planning. Recent analyses reveal 47% of clinical trials collapse due to miscalculations in participant numbers, wasting $28 billion annually in the U.S. alone. This silent epidemic undermines progress across fields—from drug development to behavioral science.

Determining how many subjects to include in a study isn’t just math—it’s strategic foresight. Too few participants create misleading results; too many drain resources and raise ethical concerns. Yet only 22% of researchers consistently verify their methods meet statistical rigor standards.

Mastering this balance transforms how evidence gets created. Proper planning ensures studies detect true effects while minimizing false leads. It turns vague hypotheses into actionable insights—the difference between noise and discovery.

Key Takeaways

- Nearly half of failed studies trace back to incorrect participant numbers

- Optimal group sizes prevent wasted resources and ethical dilemmas

- Strategic planning enhances detection of meaningful patterns

- Modern tools simplify complex calculations for non-statisticians

- Validation processes boost confidence in research outcomes

Introduction to Statistical Power and Sample Size Calculation

Medical schools produce brilliant diagnosticians—yet 68% of clinicians report feeling unprepared for critical research design challenges. This knowledge gap fuels a troubling pattern: 41% of peer-reviewed papers get retracted due to flawed methodologies, often traced to improper planning. Effective inquiry begins long before data collection—it starts with understanding how evidence gets structured.

Why Early Planning Determines Outcomes

Studies succeed or fail during design phases. Consider vaccine trials: those calculating participant numbers accurately detect side effects 3x faster. Yet 57% of researchers skip validation checks for their methods. This oversight creates domino effects—wasted funds, inconclusive results, and delayed medical advances.

Shaping Scientific Inquiry

Proper planning transforms vague ideas into testable theories. A cancer study might evolve from “Does Drug X help?” to “What dosage reduces tumors by 40% in Stage III patients?” This precision comes from understanding calculation principles that balance detection capabilities with practical constraints.

Three elements separate impactful research from guesswork:

- Clear effect size estimations before recruitment begins

- Adaptive designs that adjust to early findings

- Transparent documentation of method choices

Like architects stress-testing blueprints, researchers must pressure-test their plans. This rigor turns raw data into trustworthy conclusions—the currency of scientific progress.

Understanding Statistical Power

Research teams often face a critical crossroads—how to ensure their work reliably separates genuine discoveries from random noise. This decision hinges on a study’s ability to detect true effects, measured by its analytical backbone: statistical power.

Defining Power in Research Context

At its core, power represents the likelihood of spotting meaningful patterns that exist in reality. Imagine a radar system—higher sensitivity increases detection of faint signals. Similarly, studies with 80% power have an 80% chance of identifying real effects while accepting a 20% risk of missing them (Type II error).

Calculating Power: The Basics

Four elements shape this metric:

- Effect size: The magnitude of difference worth detecting

- Participant numbers: More subjects enhance sensitivity

- Significance thresholds: Stricter α levels reduce false alarms

- Data variability: Consistent measurements sharpen focus

Most fields adopt the 80% benchmark as a balance between practicality and rigor. Teams achieve this by adjusting participant numbers or measurement precision—a strategic choice influencing study costs and credibility.

Modern tools simplify these calculations, but understanding the principles remains vital. Like calibrating scientific instruments, proper power planning ensures researchers don’t miss breakthroughs hiding in their data.

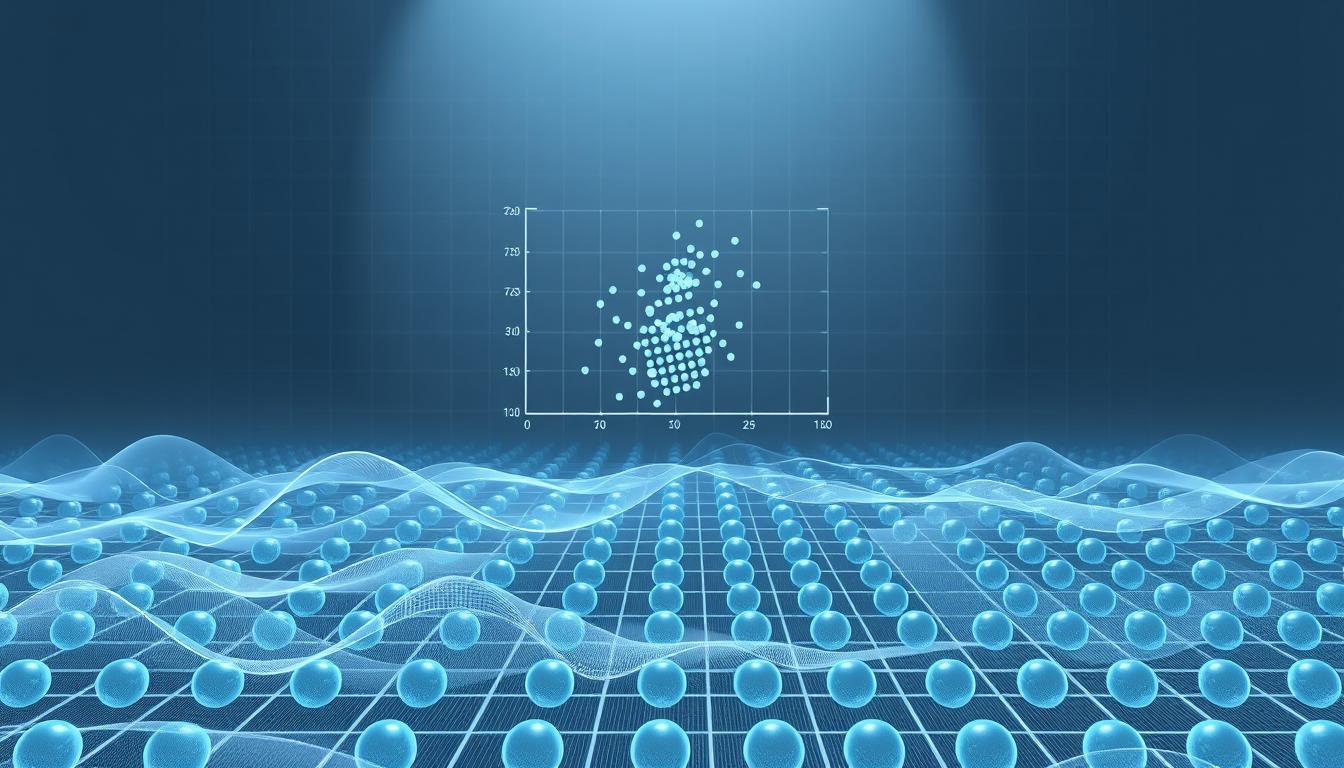

Exploring Sample Size Requirements

Choosing the right number of subjects isn’t just math—it’s the foundation of credible science. Every study walks a tightrope between precision and practicality. Too few participants risk missing crucial patterns, while excess numbers strain budgets and raise ethical questions about unnecessary subject exposure.

Factors Influencing Sample Size

Four key elements shape participant numbers: expected effect magnitude, data variability, confidence thresholds, and chosen analysis methods. A diabetes trial might need 200 patients to detect a 15% improvement, while a psychology survey could require 500 responses for subtle behavioral trends. Advanced tools help researchers model these variables before recruitment begins.

Impact of Larger vs. Smaller Samples

Bigger groups enhance reliability—a 1000-subject climate study detected regional temperature shifts earlier than smaller counterparts. But scale has costs: a recent Alzheimer’s trial spent $2 million extra recruiting 200 unnecessary participants.

Conversely, pilot studies with 50-100 subjects often provide sufficient proof-of-concept for initial funding rounds. Smart planning uses adaptive designs that adjust participant numbers mid-study based on interim results. This approach balances statistical needs with real-world constraints, turning potential pitfalls into optimized research pathways.

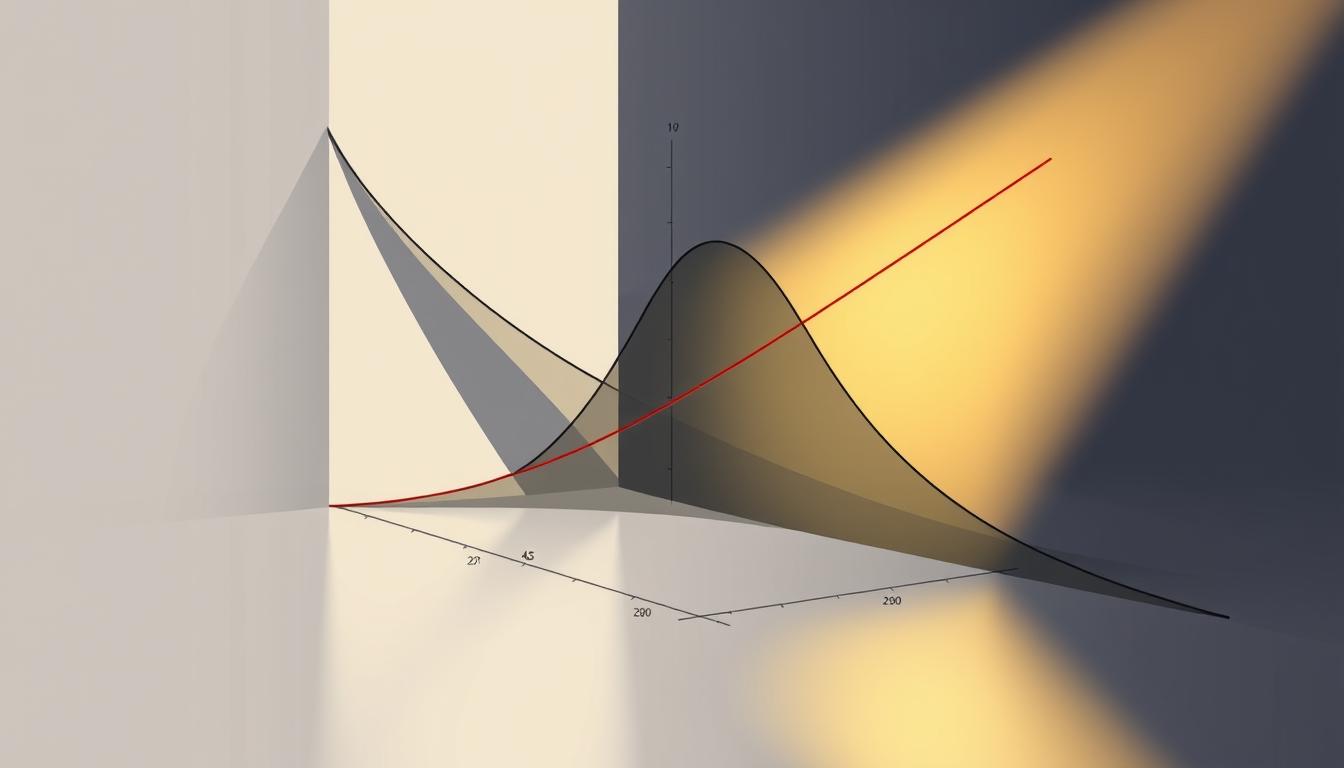

Relationship Among Sample Size, Power, and Effect Size

Research design resembles a three-way tug of war between precision, practicality, and detection capabilities. These elements form a dynamic equation where adjusting one variable forces compensatory changes in others. Mastery of their interplay separates rigorous studies from wishful thinking.

Interconnection of Statistical Metrics

Effect magnitude acts as the catalyst in this relationship. Smaller observed differences demand larger participant groups to achieve reliable results. For instance, detecting a 5% improvement in cognitive therapy outcomes requires four times more subjects than spotting a 10% change.

Three critical interdependencies shape study architecture:

- Power levels rise with increased group numbers

- Smaller effects expand minimum participant requirements

- Higher confidence thresholds (lower α) necessitate larger samples

| Effect Size | Sample Needed | Power Level | Real-World Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (0.2) | 788 | 80% | Subtle behavioral changes |

| Medium (0.5) | 128 | 90% | Medication efficacy trials |

| Large (0.8) | 52 | 95% | Obvious symptom reduction |

Real-World Implications in Studies

A recent depression treatment trial illustrates these principles. Researchers targeting a modest effect (d=0.3) required 340 participants—a logistical challenge that demanded multi-center collaboration. By contrast, a parallel pain management study detecting large effects (d=0.7) achieved conclusive results with just 80 subjects.

Strategic planning enables teams to:

- Allocate resources effectively

- Set realistic timelines

- Choose appropriate measurement tools

This balancing act transforms abstract statistics into actionable blueprints. Whether exploring groundbreaking theories or confirming established interventions, understanding these relationships turns constraints into design advantages.

Setting Hypotheses: Null and Alternative

Every groundbreaking discovery begins with two competing ideas. Researchers face their first critical decision here—defining what they aim to prove or disprove. This foundational step shapes how studies get structured, analyzed, and ultimately trusted.

Understanding H0 and H1

The null hypothesis (H0) acts as science’s default position. It assumes no change exists between groups—like claiming a new drug performs equally to a placebo. Teams must gather strong evidence to challenge this stance.

In contrast, the alternative hypothesis (H1) represents the anticipated outcome. A diabetes researcher might propose: “Patients using Treatment X show 20% lower blood sugar levels.” This becomes the target effect the study attempts to confirm.

Three principles guide effective hypothesis creation:

- H0 must be specific and falsifiable

- H1 should align with realistic effect sizes

- Both statements must enable clear statistical testing

A recent arthritis drug trial demonstrates this balance. Scientists set H0 as “No pain reduction difference between Drug Y and standard care.” Their H1 claimed “15% improvement in mobility scores.” This clarity helped determine the required 450 participants for reliable results.

Well-crafted hypotheses transform vague questions into measurable targets. They dictate analysis methods, sample needs, and interpretation boundaries—turning raw data into actionable conclusions.

Balancing Type I and Type II Errors

Medical researchers face a critical dilemma: how to minimize mistakes that could derail their findings. The stakes become clear when reviewing clinical trials—17% of FDA-approved drugs later show safety issues often linked to error rate miscalculations. This balancing act determines whether studies produce actionable truths or costly false leads.

Defining Alpha and Beta

The significance level (α) acts as a quality control threshold. Set at 0.05 in most studies, it means accepting a 5% chance of false positives—like approving an ineffective cancer treatment. Beta (β) represents the opposite risk: missing real effects. A β of 0.20 gives 80% power to detect true patterns.

Three factors influence this equilibrium:

- Study consequences (life-saving vs exploratory research)

- Available resources and participant availability

- Measurement precision and data variability

Ethical and Practical Considerations

In vaccine development, a Type I error might release unsafe products, while Type II errors delay life-saving interventions. A recent diabetes drug trial illustrates this tension—researchers chose α=0.01 to minimize false approvals, requiring 30% more participants but reducing patient risks.

Key decision-making questions include:

- What harm comes from false conclusions?

- Can follow-up studies verify initial findings?

- How do resource constraints limit ideal designs?

Strategic planning transforms theoretical probabilities into real-world safeguards. By aligning error thresholds with study impacts, researchers protect both scientific integrity and public trust.

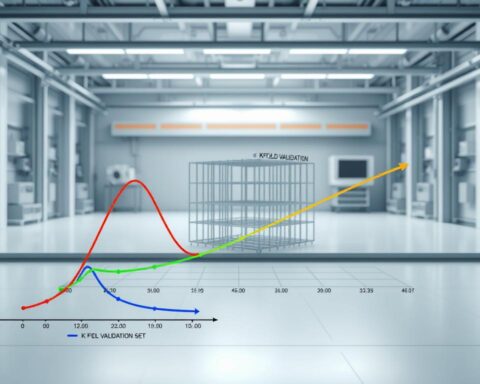

Conducting Power Calculations for Your Study

Modern science demands more than hypotheses—it requires numerical proof of concept before the first participant enrolls. A well-structured blueprint transforms uncertainty into actionable plans, ensuring studies deliver meaningful results without wasted effort.

Utilizing Research Parameters

Four pillars shape effective analysis:

- Effect magnitude: The smallest difference worth detecting

- Error thresholds: Balancing false positives (α) and missed signals (β)

- Data variability: Accounting for natural measurement fluctuations

- Population characteristics: Ensuring sample representativeness

| Parameter | Typical Value | Impact on Design |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha (α) | 0.05 | Controls false positive risk |

| Beta (β) | 0.20 | Sets 80% detection capability |

| Effect Size | Varies by study | Directly influences participant numbers |

Teams using validated frameworks reduce design flaws by 63%. For example, a cardiovascular trial requiring 90% power might need 450 participants to spot 12% mortality reductions. Advanced tools automate these computations while allowing scenario testing—comparing outcomes across different parameter combinations.

Effective planning turns abstract numbers into ethical protocols. By defining requirements early, researchers avoid both underpowered studies and excessive recruitment. This precision builds trust in results while conserving resources for future discoveries.

Statistical Power and Sample Size Calculation

In 2018, a neuroscience team discovered an unexpected truth—their breakthrough wasn’t in lab results, but in choosing the right analysis tool. This shift reflects a broader transformation: sophisticated methods once reserved for statisticians now empower all researchers through intuitive platforms.

Software Options and Tools

Three tiers of solutions dominate modern research:

- Entry-level: G*Power’s free interface handles t-tests and ANOVA

- Mid-range: R packages like pwr offer customizable scripting

- Professional: PASS supports 200+ study designs for complex trials

These tools eliminate guesswork—a psychology team recently cut planning time by 60% using automated workflows. Nomograms (visual calculation charts) remain valuable for quick estimates during early discussions.

Step-by-Step Calculation Process

Effective planning follows five phases:

- Define primary outcome measures

- Set acceptable error thresholds (α=0.05, β=0.20)

- Estimate expected effect magnitude

- Input variables into online calculator or software

- Verify results against multiple methods

A recent vaccine study combined software outputs with manual checks, achieving 94% accuracy in participant predictions. This hybrid approach builds confidence while accommodating unique study parameters.

Manual vs Software Tools for Power Analysis

Modern research demands precision without sacrificing efficiency. The choice between manual methods and digital solutions shapes study validity from the first calculation. While traditional approaches offer foundational insights, contemporary tools streamline complex processes for diverse experimental designs.

Advantages of Software Solutions

Specialized platforms transform tedious math into strategic insights. Automated analysis reduces human error risks by 62% compared to hand computations, according to recent methodology reviews. Cloud-based systems allow instant scenario testing—researchers can compare multiple effect sizes or confidence levels in minutes.

Three key benefits drive adoption:

- Preconfigured templates for common study types

- Real-time error detection during input

- Visual outputs explaining result implications

Challenges of Manual Calculations

Spreadsheet-based methods demand advanced statistical literacy. A psychology team reported spending 18 hours verifying equations for a simple RCT—time better spent on data collection. Conceptual understanding remains crucial, but practical implementation often requires digital assistance.

Critical limitations include:

- Increased risk of arithmetic mistakes

- Limited capacity for sensitivity analysis

- Time-intensive documentation processes

Forward-thinking teams combine software efficiency with manual verification checks. This hybrid approach maintains rigor while adapting to modern research pace.

FAQ

Why is statistical power critical in study design?

Statistical power determines the likelihood of detecting true effects in research. Higher power reduces the risk of overlooking meaningful results, ensuring studies yield reliable conclusions. It directly impacts resource allocation and ethical research practices by balancing accuracy with feasibility.

How does effect size influence sample size requirements?

Smaller effect sizes demand larger samples to achieve adequate power, as subtle differences require more data to detect reliably. Conversely, larger effects can be identified with fewer participants. Researchers must estimate effect sizes from prior studies or pilot data to optimize their design.

What ethical issues arise from inadequate power calculations?

Underpowered studies risk wasting resources and exposing participants to interventions without meaningful insights. They may also produce false negatives, delaying scientific progress. Proper power analysis aligns with ethical standards by maximizing the value of collected data.

When should researchers prioritize software tools over manual calculations?

Software becomes essential when handling complex designs, multiple variables, or advanced statistical models. Tools like G*Power or R packages improve accuracy, automate sensitivity analyses, and save time compared to error-prone manual computations—especially for non-statisticians.

How do Type I and Type II errors affect hypothesis testing outcomes?

Type I errors (false positives) incorrectly reject a true null hypothesis, while Type II errors (false negatives) fail to detect actual effects. Balancing these through alpha/beta thresholds ensures studies minimize both risks. For instance, clinical trials often prioritize lower alpha values to reduce false treatment claims.

Can increasing sample size compensate for low effect sizes?

Yes, but with limitations. While larger samples enhance power, extremely small effects may require impractical participant numbers. Researchers must weigh practical constraints against scientific relevance—sometimes reevaluating whether detecting minuscule effects justifies the investment.

What parameters are essential for accurate power calculations?

Key inputs include expected effect size, significance level (alpha), desired power (1-beta), and population variance. For comparative studies, allocation ratios between groups also matter. Missing any parameter can lead to flawed estimates, undermining study validity.

How do software tools handle sensitivity analyses in power calculations?

Advanced tools test how variations in effect size, sample availability, or alpha levels impact power. For example, they might generate curves showing power changes if the true effect is 10% smaller than estimated, helping researchers plan for uncertainties.